A masked figure comes to cleanse a room of the plague (detail), woodcut by V. Solis, unk.

A masked figure comes to cleanse a room of the plague (detail), woodcut by V. Solis, unk.

Introduction

In the opening lines of the Decameron, Boccaccio introduces his [female] readers to the dreadful place and time in which he has set his story:

"Every time I stop to consider your natural inclination to pity, most gracious ladies, I recognize that you will find the opening of this present work abhorrent and distressing; for so is the painful recapitulation of the recent deadly plague, which occasioned hardship and grief to everyone who witnessed it or had some experience of it, and which marks the introduction of my work."

The author then takes a moment to acknowledge the leading theories of the Plague's origins--astrological or divine--and its initial effect on society:

"Whether it was owing to the action of the heavenly bodies or whether, because of our iniquities, it was visited upon us mortals for our correction by the righteous anger of God, this pestilence, which had started some years earlier in the Orient, where it had robbed countless people of their lives, moved without pause from one region to the next until it spread tragically into the West. It was proof against all human providence and remedies, such as the appointment of officials to the task of ridding the city of much refuse, the banning of sick visitors from outside, and a good number of sanitary ordinances... As the said year turned to spring, the plague began quite prodigiously to display its harrowing effects."

"And the plague gathered strength as it was transmitted from the sick to the healthy through normal intercourse, just as fire catches on to any dry or greasy object placed too close to it. Nor did it stop there: not only did the healthy incur the disease and with it the prevailing mortality by talking to or keeping company with the sick--they had only to touch the clothing or anything else that had come into contact with or been used by the sick and the plague evidently was passed to the one who handled those things."

There were some who inclined to the view that if they followed a temperate life-style and eschewed all extravagance they should be well able to keep such an epidemic at bay. So they would form a group and withdraw on their own to closet themselves in a house free of all plague-victims; here they would enjoy the good life, partaking of the daintiest fare and the choicest of wines--all in the strictest moderation--and shunning all debauchery; they would refrain from speaking to anyone or from gleaning any news from outside that related to deaths or plague-victims--rather did they bask in music and such other pleasures as were at their disposal.

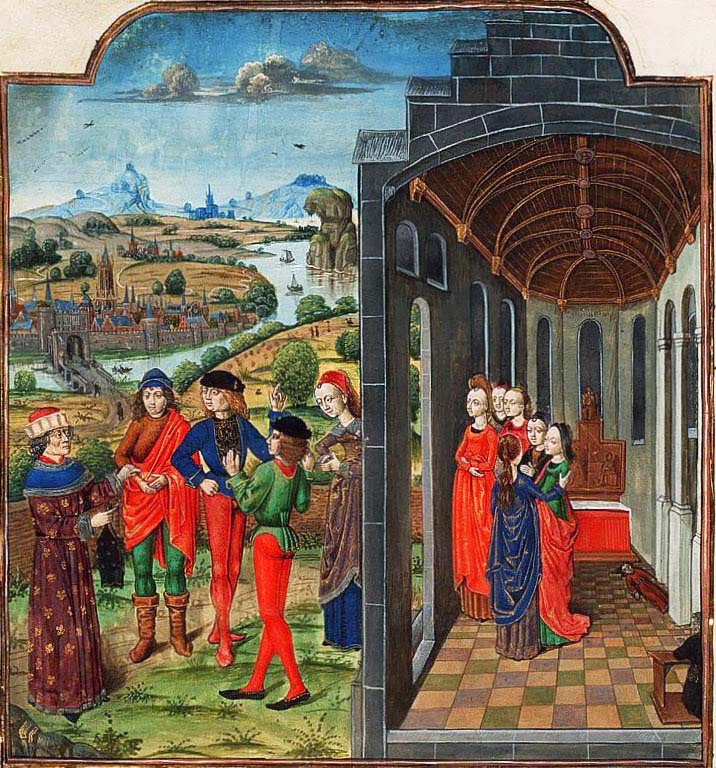

Illusration from The Decameron Inroduction (detail), by Taddeo Crivelli, 1467.

Illusration from The Decameron Inroduction (detail), by Taddeo Crivelli, 1467.

Florence is then described as a city where 'the laws of God and men had lost their authority' due to the absence of any law enforcement. Families deserted their dead, instead choosing to pay 'people of the commonest sort' calling themselves "undertakers" to bear them to the grave. After graveyards reached their saturation points, 'enormous pits were dug' and the fresh corpses were stacked like 'goods are stowed in a ship's hold'. Boccaccio then introduces his characters and has them forsake the city in favor of the country.

"In my view the best thing we can do in our present situation is to leave the city, as so many have done before us and are still doing, and go to our country estates--each one of us has a good choice of these. ... There we can hear the birds sing, and watch the hills and plains turn green; there are fields like a sea of waving corn, and all sorts of trees, and a nice open sky to look at: the heavens may be scowling at us but they still won't refuse us their glimpse of eternal beauty--and that's a great deal more beauty than we'll ever find staring at the empty buildings in this city! The air is much fresher, there's far more of all the basic necessities of life that one needs at a time like this, and not as many difficulties to contend with."

After reaching the villa, the leading lady, Pampinea proposes that each one have a turn being appointed as the leader, 'someone to honor and obey as [their] sovereign'. Naturally, she is unanimously elected queen for the first day. They made a garland to remain the 'outward sign of royal imperium'. After an exquisite meal and mid-day 'siesta', the entire company came together in the meadow where the queen made the suggestion of entertaining themselves with stories while awaiting the heat of the day to abate:

"It's lovely and cool here and there are games tables with chess sets, as you see, and you can all amuse yourselves as the fancy takes you. But with these games, one player's bound to get upset, which is not all that much for the other or for the onlookers; so if you follow my advice, we shall spend this sultry part of the day not playing games but telling stories: in this way one narrator entertains the entire company."

Next: The Decameron, Day One

Reference:

Boccaccio, Giovanni. The Decameron, translated by Guido Waldman. Oxford University Press, 1993.