Danse Macabre (detail), by Bernt Notke, c1440-1509.

Danse Macabre (detail), by Bernt Notke, c1440-1509.

Florentine-style Quarantine

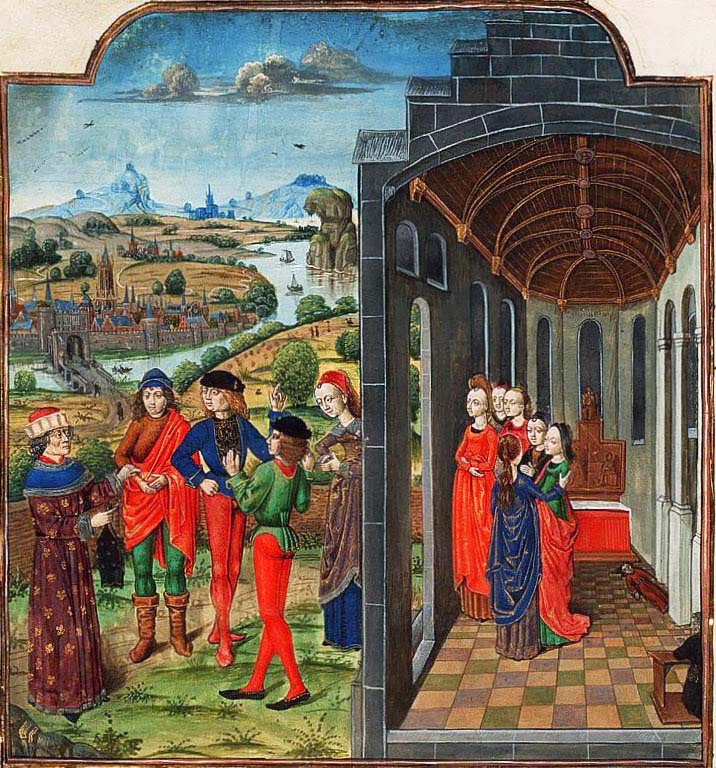

What advice could our medieval ancestors possibly have to offer in light of our current pandemic? More than you might think. About 1351, in the wake of the Black Death, Giovanni Boccacio began writing his masterpiece, the Decameron. It is the story of ten young noble men and women who decide to practice their version of "social distancing" by fleeing the city of Florence, which is being ravaged by the Pestilence, and taking shelter in a remote country villa. They spend their afternoons telling a series of one hundred tales over the course of their ten days of isolation.

Although we often give a great deal of attention to medieval man's lack of modern understanding about germs and the transmission of disease, there is still much wisdom that can be gleaned from writings from the period. The Great Mortality claimed between 30-60% of Europe's population and some estimates claim more than 100 million died worldwide in a matter of 2 or 3 years. In fact, it took Europe over two centuries to recover to its pre-1348 population.

St. Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken (detail), by Josse Lieferinxe, c1497-1499.

St. Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken (detail), by Josse Lieferinxe, c1497-1499.

Author's Foreward

Boccaccio explains in his own words his motivation to write the Decameron: Love. He credits his survival to his friends and their support. Although his sorrows may have come to an end with the passing of the Plague, he is not forgetful of their past favors and 'nothing short of death' would erase those memories. His characters, he explained, were chiefly women, because Love leaves often leaves them 'condemned to remain gloomy' without 'some fresh distraction' like his manuscript.

"It is inherently human to show pity to those who are afflicted; it is a quality that becomes any person, but most particularly is it required of those who have stood in need of consolation and have obtained it from others; now if ever there was a man who craved pity or valued it or rejoiced in it, that man was I."

"If a man is down in the dumps or out of sorts, he has any number of ways to banish his cares or make them tolerable; he can go out and about at will, he can hear and see all sorts of things, he can go hawking and hunting, he can fish or ride, gamble or pursue his business interests."

"I will to some degree make amends for her [Fortune's] sin [of making women the weaker sex]: to afford assistance and refuge to women in love—the rest have all they want in their needles, their spools and spindles—I propose to tell a hundred tales (or fables or parables or stories or what you will). Thy were narrated—as will transpire—in the course of ten days by a goodly company of seven ladies and three young men which assembled during the last incidence of the plague.

Reference:

Boccaccio, Giovanni. The Decameron, translated by Guido Waldman. Oxford University Press, 1993.