The previous assertion should not be taken to mean that the vast majority of armour was hideously ugly or completely un-fashionable. At least some were elaborately painted, perhaps to distinguish the wearer’s company, while others were coated in a heavy lacquer that helped to prevent rust.

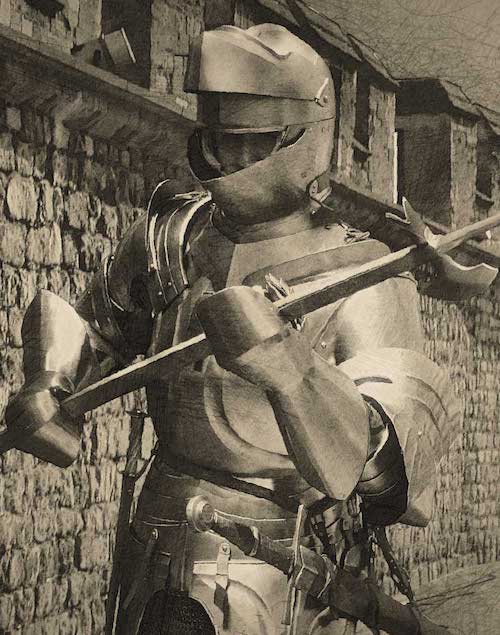

Nobles with much richer tastes could not only commission ‘white armour’ that was polished to a mirror-like finish, but they also could have the steel blued, decorated with intricate etchings or even, in the case of royalty, completely gilded. After all of the pieces of a harness were completed and the work approved by the master armourer, everything would be sent to the polishers before being strapped and assembled.

So why would anyone pay five times as much for a harness that provided the exact same protection? Armour, like civilian attire, was a direct representation of its wearer’s social status. Sumptuary laws passed in 1336 forbade all but the royal family from wearing cloth of gold and purple silk; the wife of a poorer knight could not wear fur; and, only those of the knightly class or above could have gilt spurs, hilts, etc.

It was not all vanity and class distinction, however. On the battlefield, expensive armour could be something of a life insurance policy. What man would willingly kill a rich noble wearing a harness that was etched and gilded? His family would obviously have the means to pay a small fortune in order to guarantee his safe return.